I’ve had this letter sitting in my Drafts folder for several months, which feels apropos. Interruptions are everywhere these days (hence the long period of silence over here), and this one never quite felt “done enough.” Though it still doesn’t, I realised that’s the point. Embracing a fragmentary relationship to writing and making in early motherhood, I’m sending this to you, at the beginning of a disorienting year on scales from the personal to the collective*, in case you too are in a season of constraint, interruption, and limitation, and care about not abandoning your creative practice in its midst, but are—like me—wondering: HOW?

*I’m choosing to write about creativity, art, and intellectual work in this fraught and frankly terrifying geopolitical moment because I think it is one of our foremost means of resistance

An auspiciously-timed overlap between returning to full-time paid work at the university in September and prolonged periods of very limited sleep in babyland this autumn and winter have had me thinking a lot lately about exhaustion, limitation, constraints, interruption, and how these relate to creative work.1

I’m not sure anyone is creatively resourced, let alone resourced at all, in the throes of sleep deprivation. Weeks of extremely little / nonexistent sleep never fail to bring me face-to-face with my more desperate states of being. Tobias joked that I should tattoo the question—“Have you slept?”—on my wrist and if the answer is “No,” or even, “Barely,” then to not believe any of my thoughts. It was the first tattoo I seriously considered getting.

But when thoughts and ideas are the currency of my work, I don’t have much of a choice whether to believe (or at least confront) them, regardless of how the night(s) before went. Meeting my mind those first weeks “back” (a word I’ve grown to rue since having a baby) at work was humbling and, at times, shocking. I read lines over and over, not quite processing their meaning. I dreaded the blankness I’d encounter mid-sentence in a meeting. My mind felt foreign to me, estranged.

It was all something that, if you’d told me would happen prior to becoming a mother, would have confirmed my fears. AND it’s something I hesitate to write about, lest it play too easily into the trope of the “baby brain,” which has been used to diminish creative and intellectual work done by parents (I love returning to Nada Alic’s essay by the same name for how it turns this trope on its head). Brains, like experiences and conditions of motherhood, are plastic and diverse and intimately entwined with their environments (there’s so much incredible emerging research about the maternal brain), none of it is ever all one thing, as quickly as something sediments it evaporates into something else… and the last thing I want to insinuate is that the work of parenting is not also deeply intellectual or creative. I’ve found it to be immensely both—just in a different form than I’ve ever experienced and am still coming to understand.

Coupled with the fracturing I felt, still feel, at work—relishing a different form of stimulation, yet always wondering what my daughter is up to across the bridge at home (with her father, bless Swedish parental leave), feeling FOMO for what feels like a particularly exciting time in her development and emerging personhood, missing her in an aching, physical way that isn’t receding with time, wanting to split myself in two—I am left wondering how to inhabit my new reality and integrate it with my approach to (creative) work.

I’m also noticing an internalised ableism in relation to my profession, something I didn’t see before from the faraway land of fairly dependable sleep and domestic care work that basically only centred upon one person (myself). It’s an ableism that requires so many base, invisible conditions to be met—conditions I took for granted until I found myself unable to meet them.

It’s become clear my old paradigm (overwork, perfectionism) will eat me (and by extension the ones I love and care for) alive. Yet, still in the process of finding a new way, it’s still my default mode. I’m finding the recalibration incredibly difficult. I don’t know what creativity is—what my creativity is—in this still-new, disorienting state.

Whenever we feel ourselves coming up against the walls of our capacity, when our lives deviate from the conditions we imagine to be ideal (or even necessary) for our creative work, we can ask:

To what standard or baseline am I comparing myself?

What is the refraction through which my current state comes to be called “depleted” or “compromised” or “not enough”?

Can I get curious about the refraction itself?

Often—and we have a long history of feminist theory, critical disability studies, crip and queer theory to thank for illuminating to this—it is the monolithic paradigm of the unencumbered (white, cis-, hetero) male artist, whose work is, of course, made possible by the invisible labor of care workers, most often women.

Still, and I’m certainly not the first to say this, some of the most provocative, human, empathic, moving, urgent art comes not from enabled abundance, but from limitation.

The question, then, that dogs me is: HOW (the hell) does this art actually get made? Along with…

How does one show up to creative work from the edges of exhaustion?

How might limitation embed its own form of creativity?

What might interruption offer to, rather than subtract from, creative process?

The more I’ve started to investigate these questions, the more I’ve come to appreciate stories of how constraints and limitation are integral (rather than antithetical) to creative process. Constraints can be formal (the size of a canvas) and conditional (the unpredictable length of a baby’s nap) and both at once.

In these stories, I’ve found solace in the notion that constraint and limitation give way to something — form, substance, meaning — to the art, and to its maker. Because the making is not only about producing something to be consumed, or performing something to be beheld. It is inherently valuable as process, as heuristic, as a means to witness ourselves and our relation to the thrumming world that surrounds. The ways we are inextricable from it. To locate ourselves not in fixity, or in the mirage of a “someday” in which our conditions are stable, but in their inevitable flux.

With this instantiation of The Liminal, I wanted to create a care package of inspiration and solace to return to — for myself and for you — when trying to make art and creative work from the depths of depletion. In the face of chronic illness, injury, insomnia, pregnancy, infertility, fertility treatment, early parenthood, intensive periods of caretaking, grief, loss, this geopolitical present steeped in disorientation and fear… or any of the innumerable human maladies and joys of living we all find ourselves in, for chapters of life both brief and interminable. To locate in our exhaustion glimmers of raw material. To slough off the perfectionist inner critic because, honestly, we are just too tired for that shit. To notice the ways being in an altered state—in our bodies, in our minds, in our lives—can offer a way of seeing the world and each other slightly askance. Is that not what art, too, aspires toward?

I want to be clear, in offering these perspectives, I’m not promoting or celebrating the late-capitalist virus of overwork or productivity-at-all-costs that denies the absence of structural support for people living on edge. Nor am I ignoring the importance of defending the human right to rest (a right that is unfortunately more of a privilege, distributed all too unevenly along axes of social inequality).

Rather, embedded in all this is a gnawing curiosity: about whether and how the conditions under which creative work is made—constraints and all—can become part of the art itself. I suppose that is the “how” I’m searching for. The human stories behind the art, made not in spite of constraints but because of them, that maybe are the real work of art itself.

Below are a few morsels of inspiration from artists working openly with constraints.

Maggie Nelson, on writing by any means necessary —

In an earlier patch of sleep deprivation last summer, I read Nelli Ruotsalainen’s interview with one of my favourite authors, Maggie Nelson, in Tulva — a Finnish feminist magazine — about writing and motherhood and interruption.

In response to Ruotsalainen’s question about how Nelson wrote The Argonauts (one of my favourite books) in the early days of caring for a baby, Nelson responds:

…this question of interruption is really fascinating, because it taps into one of these ideas we have about unfettered genius, and what it needs, and what it looks like—you know, these patriarchal fantasies in which a man writes for hours in solitude, unencumbered by any other obligations. We all probably need and want uninterrupted periods of time to write... And yet, very few people throughout history have actually had that. And a book written while a baby naps is not a degraded book, it’s not a book that didn’t have presence of mind, and thus had to come out in little dribbles. It’s a book that did what writers have done since time immemorial, which is write by any means necessary.

Confronting the often-reductive language surrounding motherhood and the trope of the “baby brain,” Nelson goes on to say:

It’s difficult to pay homage to the true difficulty of finding time to concentrate, and to the changes in time and mind that infant-rearing can occasion, while also not indulging this idea of mothers having mush-brains. Also, there are a lot of things in life that alter our neurological state. Sedgwick for example wrote a lot about chemo-brain. That chemo can create a kind of fog that she would wade in and out of as she struggled with cancer for 15-18 years. Chronic pain affects our writing too—think of Nietzsche and his debilitating headaches! People are moving in and out of a lot of spaces and states a lot of time, and—I guess this is the majoritarian in me—but I would rather we folded motherhood into these rather than marking it as this one really singular, disruptive thing to intellectual life.

Sarah Ruhl, on not thinking of life as an intrusion

Every time I find myself tempted by the siren song that pits writing and parenting against one another, I return to this quote from playwright Sarah Ruhl’s aptly titled 100 Essays I Don’t Have Time to Write:

I found that life intruding on writing was, in fact, life. And that, tempting as it may be for a writer who is a parent, one must not think of life as an intrusion. At the end of the day, writing has very little to do with writing, and much to do with life. And life, by definition, is not an intrusion.

Lidia Yuknavitch, it’s “not when you’re feeling fancy and smart” —

One of my favourite writing exercises (introduced to me by friend and mentor Chloé Caldwell) is this braiding exercise from Lidia Yuknavitch (another beloved author). My favourite part of the video is when Lidia says:

I actually believe your best writing comes when you've exhausted yourself, and not when you're feeling fancy and smart and know what you're doing and everything's easy.

She calls this an act of excavation, an act of labor.

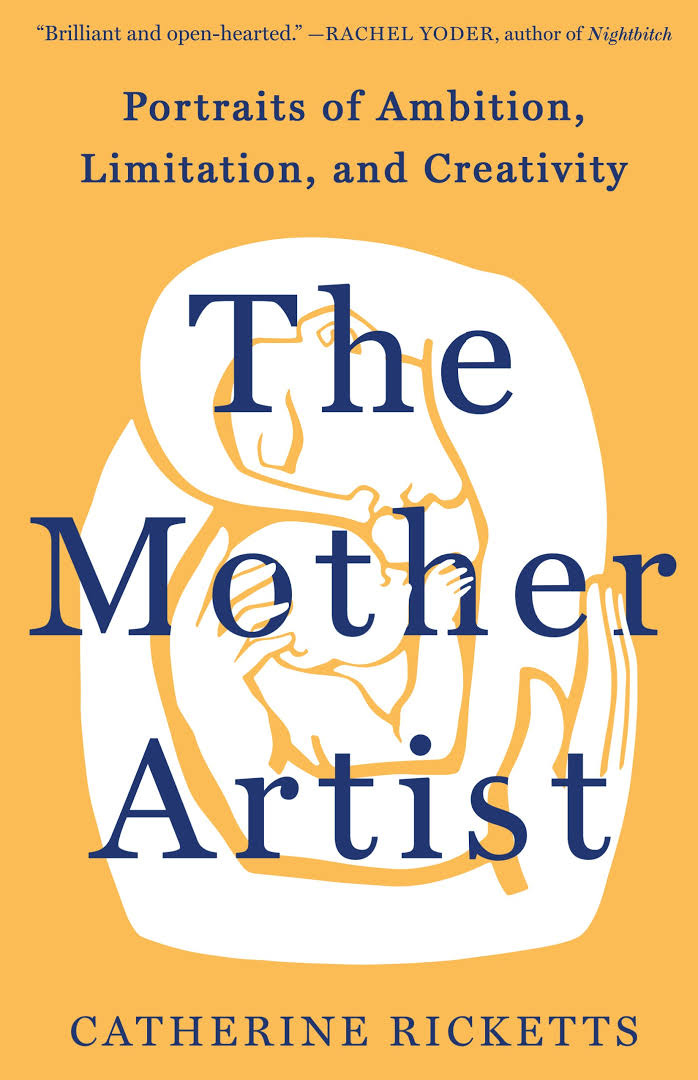

Early in my postpartum, I read The Mother Artist by Catherine Ricketts, and I highlighted almost the entire book on my Kindle during midnight breastfeeds. I have been meaning to return to it ever since. The work is animated by two main questions:

How are motherhood and artmaking at play and at odds in the lives of women? What can we learn about ambition, limitation, and creativity from women who persist in doing both?

Ricketts intimately examines the art and lives of artist-mothers such as Alice Neel, Toni Morrison, Joan Didion, and Madeleine L’Engle, interwoven with her own story.

A number of brilliant Substacks regularly engage with interruptions and limitations in conversation with creativity. Some personal favourites are:

- by

And, if reading anything or watching a video feels inaccessible right now (I get it), here are a few podcasts that explore constraints & creativity…

Ocean Vuong, on the generativity of exhaustion—

Over the years, I return again and again to

’s interview with poet Ocean Vuong on the podcast Thresholds (back for a new season in 2025, yay!), in which he says:I think exhaustion, exhaustion, you know... As a species, I think it's exhaustion and danger that creates creativity. How do I get out of here? How do I, how do I build this fish trap? You know, it's always the question. And I think that moment of… of innovating beyond your condition begins with fatigue, exhaustion and discontent.

Esmé Weijung Wang on the unexpected shapes lives take —

…and how creative work can shapeshift to meet them:

Sarah McColl on creative endurance—

This conversation with Sarah McColl, author of Joy Enough, illuminates the how of keeping going, no matter the circumstances conspiring otherwise:

also writes beautiful longform essays about overlooked and unfamous art by now-dead women on her Substack, . I was lucky to take an inspiring workshop with Sarah on caretaking and creativity and she truly reoriented my perspective on the unexpected glimmers hidden in limitation and interruption that can emerge when we center, not hide, our conditions.There is so much more to be shared and said, but I’ll leave us here for now, with a feeling that this is the beginning of a longer conversation…

Do you have any personal stories, resources, or inspirations relating to constraints, limitation, and creative work? I (and I’m sure many of you) would love to hear them — please feel welcome to share in the comments section:

desk updates —

Since I last wrote here, my essay “Big Sky” was published in Washington Square Review. It chronicles a roadtrip across the US with my father on my way to graduate school, tracing the backbone of his childhood across the Midwest. It’s also about ghosts, and the stories, histories, and intimacies of those closest to us that we do—and don’t—get to know:

I’m deeply honoured that “To the Anesthesiologist” in Off Assignment was nominated for the Pushcart Prize and Best American Essays. This means a lot to me particularly because I wrote most of it in fits and starts while my baby napped.

WITHIN, my workshop series for writing from/through/into the body, is still on pause, with aspirations for an Autumn 2025 return. You can add your name to the waitlist here to be the first to know when we begin again.

Footnotes! Late to the game, but I’m thrilled to discover Substack has them. From here on out welcome to my meta-narrative. Anyways, once I started thinking of my profession— as an anthropologist and academic — and my research as also inherently creative (in addition to my “creative-creative” work like nonfiction and essay writing), it opened up a lot for me. If your work involves generating something where it once didn’t exist, your work is creative.

Thanks so much for including me here. I love your embrace of the fragmentary!