“There are years that ask questions and years that answer”

— Zora Neale Hurston

It’s that time of year (the most wonderful?) again: when the pull to encapsulate the past twelve months into some kind of neat narrative packaging lures us temptingly, with the hopes that the turn of the calendar will bring something different, something new. Even when consciously aware of this pull, I’m certainly not immune to it, and come early December, a certain nostalgia takes foot.

Was this a year that asked you questions? A year that answered?

Until mid-summer, I thought this year was (for me) as close as it comes to the latter. But this autumn has, in so many ways, convinced me of the former. Of course, the two (questions, answers) constitute one another; one doesn’t exist without the other. And maybe what we call in the moment a “question-year” may, with the work of time and the privilege of a rear-view mirror, reveal itself to be an “answer-year” all along. Still, this particular season of life feels peak-liminal—personally, professionally, profoundly.

I’m writing you this morning—9:03am on a Friday in Malmö—with a groggy Nordic sun just hugging the horizon, the dusk-dawn winterlight that never quite breaks into its fullness, having just received some waited-for news (an “answer” of sorts) that feels at once clarifying, disappointing, relieving, and unsettling.

In my body, the exhale that was trapped somewhere in my chest for months has just allowed itself to release. This autumn has returned me to so many core themes—belonging, self-respect, will, worth, ambition, identity—and I finally feel ready to tend to the deep exhaustion left in its wake. I enter most winters, especially in Sweden, dragging my feet — a resistance acutely aware of the long haul we’re in for. But for some reason, this winter feels different, impeccably timed; for once, my inner and outer winters feel strangely in sync.

If you, too, find yourself in a liminal year-end soup-like swirl, I wanted to share with you something that’s been bringing me comfort, hope, and a sense of trust.

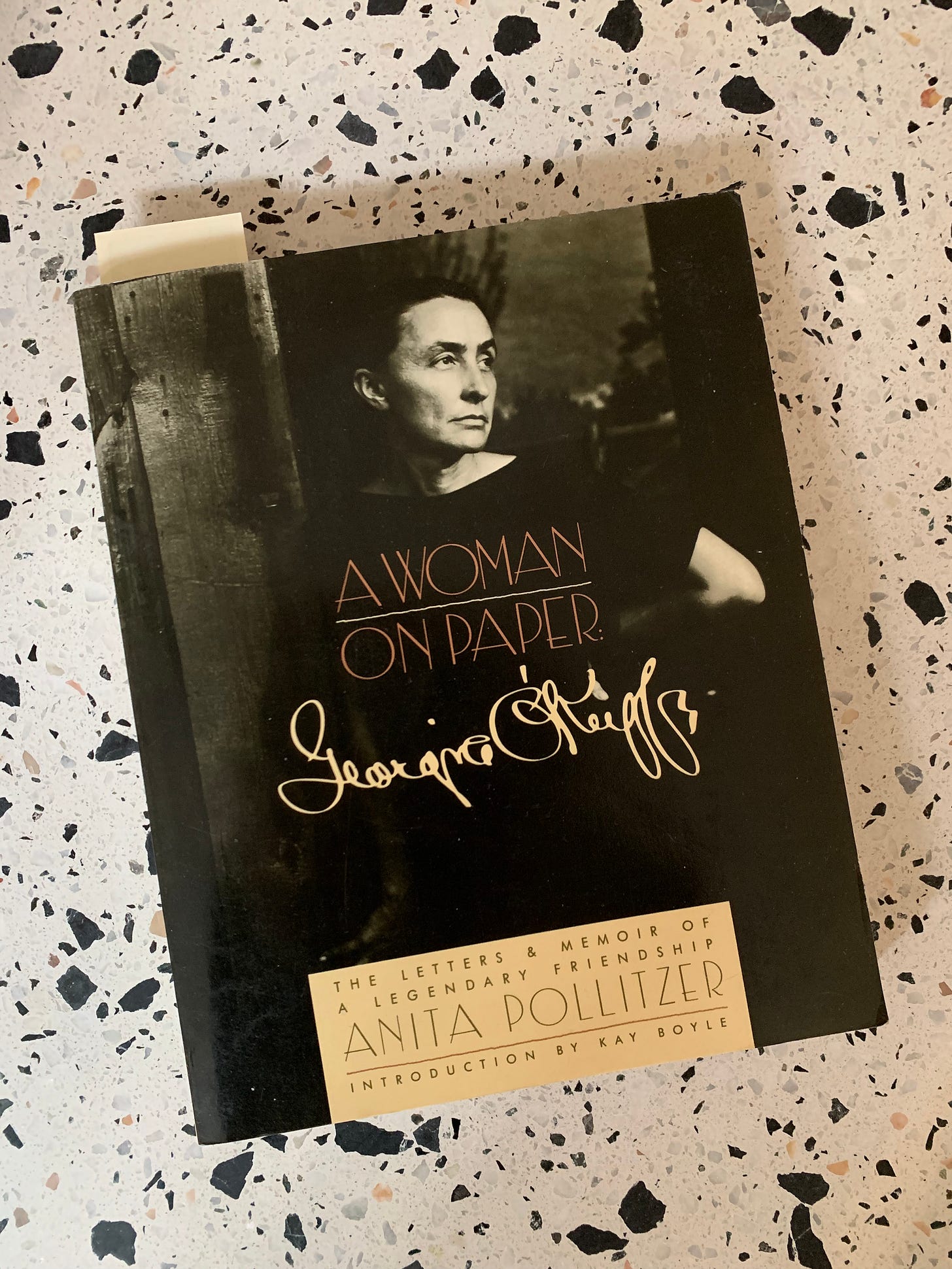

Keeping me company these days is a copy of A Woman on Paper, scored from Womb House Books (a gem of an online bookstore I recently discovered with an exceptional curation of rare, vintage books and a focus on feminist literature—check it out!).

A Woman on Paper is a collection of letters between Georgia O’Keeffe and her friend Anita Pollitzer, a rare and intimate glimpse into the artist in her becoming; her human doubts and dreams laid bare.

What’s captivated me most from this collection is not the story of Georgia O’Keeffe as we know her today—one of the most significant and singular artists of the 20th century. Rather, it’s the stories from the years of her becoming—one year in particular: 1915. A year that asked questions in its instability, that provoked and pushed her, and arguably, made Georgia into herself.

In 1915, O’Keeffe reluctantly took a teaching position at Columbia College in South Carolina, even as she longed to return to the thriving arts scene in New York. Her exchanges with Pollitzer reminded me (almost comically) of my own back-and-forth with friends as we deliberate on the precarious academic job market:

“I don’t want it—I want to go back to New York”// “Of course a College Position is not to be gotten so easily… of course you might have extra time to do work for yourself—and you might make piles of money and come up north the year after.”// “I have to make a living—I don’t know that I will ever be able to do it just expressing myself as I want to… If I can’t work by myself for a year with no stimulus other than what I can get from books—distant friends—and from my own fun in living—I’m not worth much… I have made up my mind.. Made it all up in a package—tied it with a rope and plopped on it with my heels… I will arrive at the confounded place Wednesday morning.”

What comes across reading O’Keeffe’s letters to Pollitzer over the course of 1915 is a soul that feels out of place, the agonising self-doubt that comes with really examining oneself and one’s motivations, grappling with the twin tensions of producing art for the gaze of another and for the expression of one’s poetic self.

Ultimately, it was the disquietude of this year, coming up against the edges of all the art that came before her that felt as if it were suddenly closing in… that prompted O’Keeffe to produce her first charcoal drawings and experiments in abstraction that broke with the conventions of her prior work and launched her into an era of genre-defying creation.

“In South Carolina,” writes Pollitzer, “away from art influences and previous teachers, Georgia wrote to me with dissatisfaction that she felt she was ‘still working like other people.’ … Later she stated: ‘I thought to myself, well, if that’s been done, I don’t have to do it, I guess if I’m going to do something that is my own, I’d better start."‘ … She started working, with great abandon, and entirely the way she wished.”

O’Keeffe sent these preliminary drawings to Pollitzer, who (against O’Keeffe’s wishes) showed them to Alfred Stieglitz, and the rest, as they say, was history (there is, of course, a lot more to this story, but I’ll pause here).

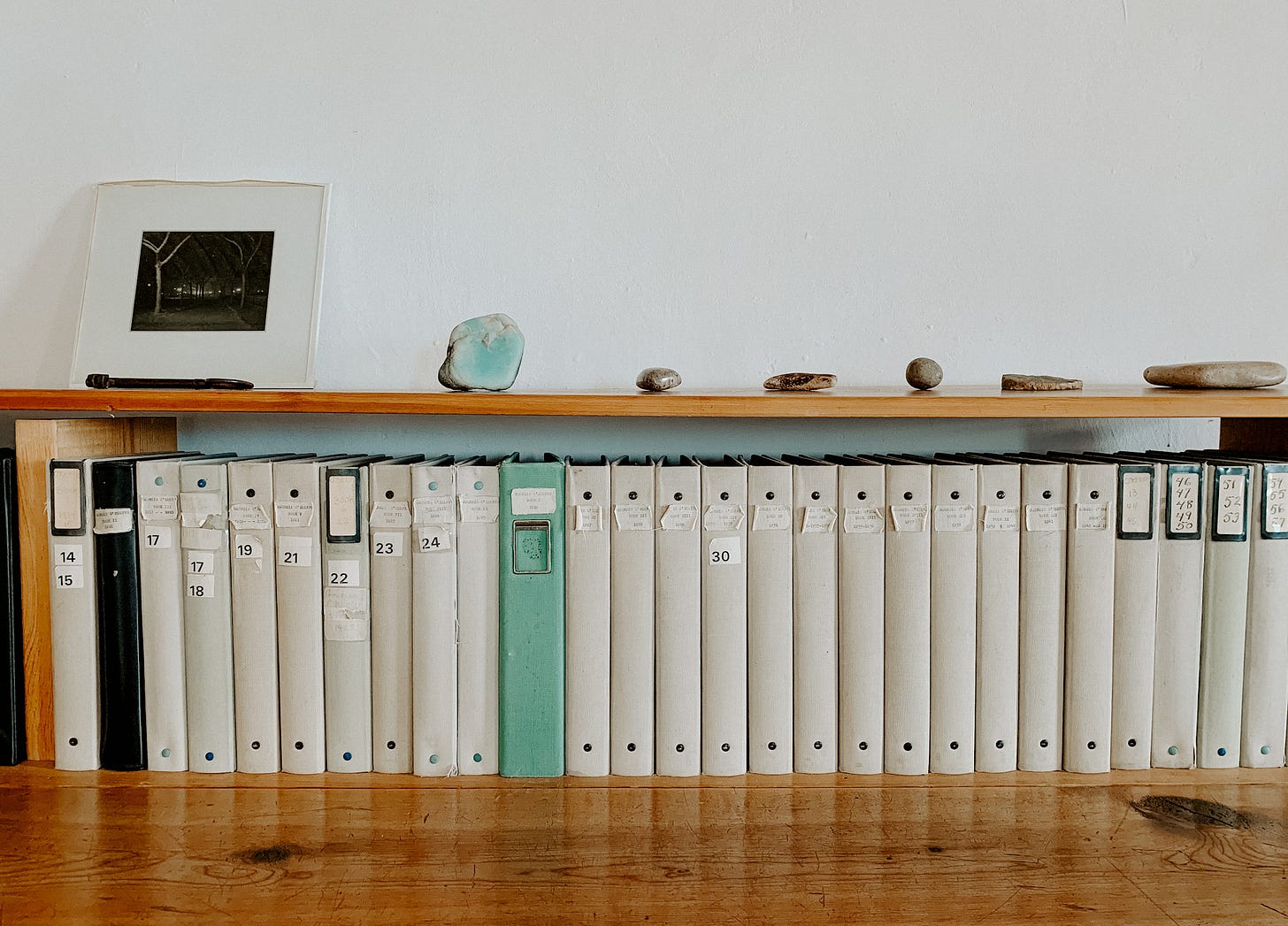

In conversation with letters snippets from 1915 that, in the rearview, revealed O’Keeffe’s artistic becoming, I’m interspersing a photo-essay I’ve been meaning to share with you for months—snaps from wandering through Georgia O’Keeffe’s home studio in Abiquiu, New Mexico (about 60 miles north of Santa Fe) earlier this fall. This compound was in total ruin when she found it, and restored with love, care, and artistry over the years 1945-1949, when she was 58-62. It was where she grew vegetables, dried homegrown spices and teas, dreamed, read, painted, and lived out her life, along with her two chow chows. It was a home entirely of her own making; a materialisation and inhabitation of her artistic vision.

Stepping into O’Keeffe’s house was like walking through the soul of an artist, materialised. Reading A Woman on Paper afterwards is like stepping into the soul in its formation, messiness, becoming. One does not exist without the other. My hope is that this reads like a conversation of becoming, the story behind the story, the questions always in ongoing conversation with what we call “the answers.”

So much gets lost when we inherit downstream images of people and things as already-made: the stories of their becoming, their turbulence and their struggle, are often erased or decentered. There’s a recuperative solace that comes with peering into the before, the becoming, that I believe profoundly connects us—with each other, and most fundamentally with ourselves, in these question years.

I hope these words and images bring you a pause, a moment to step outside the current of the everyday, a chance to reconsider the work of time, to soften into the question-years knowing, as Rilke would say, that you are all along living your way into the answer.'

Quotes below are from Georgia O’Keeffe’s 1915 letters to Anita Pollitzer at the age of 28; Photographs from her Abiquiu home, which she tended to and restored 30 years later, at the age of 58 (taken by me in September 2022)

“It is going to take such a tremendous effort to keep from stagnating here that I don’t know whether I am going to be equal to it or not… I have never felt such vacancy in my life—Everything is so mediocre—I don’t dislike it—I don’t like it—It is existing—not living… All the people I’ve met are all right to exist with, and it is awful when you are in the habit of living.”

“I don’t see why we ever think of what others think of what we do—no matter who they are—isn’t it enough just to express yourself… If I make a picture to you why should I care if anyone else likes it or is interested in it or not. I am getting a lot of fun out of slaving by myself—The disgusting part is that I so often find myself saying—what would you or… somebody—most anybody—say if they saw it—It is curious—how one works for flattery— Rather it is curious how hard it seems to be for me right now not to cater to someone when I work—rather than just express myself.”

“Anita—I just want to tell you lots of things—we all stood still and listened to the wind way up I the top of the pines this afternoon—and I wished you could hear it… I haven’t found anyone who likes to live like we do.”

“Do you feel like flowers sometimes?”

“Don’t you think we need to conserve our energies—emotions and feelings for what we are going to make the big things in our lives instead of letting so much run away on the little things every day.”

"It always seem to me that so few people live—they just seem to exist—and I don’t see any reason why we shouldn’t live always—till we die physically—why do we do it all in our teens and twenties…”

"What is Art anyway? When I think of how hopelessly unable I am to answer that question I cannot help feeling like a farce—pretending to teach anybody anything about it… What are we trying to do—what is the excuse for it all… I don’t mean to complain—I am really quite enjoying the muddle… I decided I wasn’t going to cater to what anyone else might like—why should I?”

"I thought to myself, well, if that’s been done, I don’t have to do it, I guess if I’m going to do something that is my own, I’d better start."

This letter, and your photos is a gift. And a pause. Thank you.

I started this year reading the unedited notes and journals of Sylvia Plath between 1950-1962. It landed in my heart as this deep connection, although of course this is not a person that I know personally. The journey, the becoming, the story behind the story, the struggles and pain. The very human story behind it all.

The rest of the year, other female writers have pulled me into their stories in a similar way, and I am truly greatful to witness it, through their words. Thank you for this letter, your words landed in my body.

Love,

Catrin Kjäll