I’m writing you with my somehow-4-month-old daughter on my chest, to the metronome of my keyboard and her soft milkbreath, wondering if her nap will outlast my attempt to describe what largely lives outside description. Sometimes I pause and look down at her hand, those miniature fingernails, grasping my clothes or reaching out for my wrist to pull me closer into her, and I lose my breath with the impossibility of it all. How she is here; how I am, too; how she is strong and thriving; how much more joy and meaning I am finding in all of it than I had expected to (even in the hard and humbling moments, of which there are countless).

We recently crossed the threshold of what is referred to as the “fourth trimester”—the first three months after birth, in which mother and baby exist in an intense symbiosis, swimming together in fluids (milk, tears, blood). There is a word in Swahili — mamatoto — that translates to “motherbaby,” a nod to the fact that although the baby now exists outside the mother’s womb, their two bodies are still tethered, still an organism unto itself. That is what our early days together have felt like: the boundaries between her and I blurred, my own boundaries with the world rearranging themselves in ways I have yet to understand. In her book Reproduction, Louisa Hall describes the experience of birth and early motherhood as being on the moon. This lands with me: there is something distinctly extraterrestrial about this motherbaby-ness. Cocooned in our home as if it were an entire planet, the way time stretches and warps, the absence of prior forces of gravity… it is otherworldly.

Moving from the fourth trimester into the indefinite postpartum that exists after, I’m struck how many thresholds have bled into one another these past months, thresholds I expected to be discrete events: the final days of pregnancy, the days (yes, days) of giving birth, the first raw and tender days of her life. The seasons this year bled into one another, too, in the feverdream of our first weeks. She arrived in the belly of Winter, now it is decidedly Spring (nearly Summer). Nature is waking up to itself and she is waking up to the world, her head on a swivel, her vision consolidating, her eyes wide with the newness of it all, as if everything in the world is a surprise, which it is. I feel like I’m waking up to the world too, for a second time. I try to see it all through her eyes: What would it be like to go from total darkness to this? It is a wonder to me that we all have; it is a wonder to me that none of us remember.

Back when all of this was only theoretical, during the years of contemplating this thing of “motherhood” in the abstract, and even during the months of her growing inside me, much of it worried and scared me. To be so intimately and irrevocably wound into another. How this would force me to relinquish, or at the very least redefine, my ways of moving about the world. And it has, and still is, in ways I can’t yet begin to understand.

But living “it” in the concrete, what I realise was missing from all of my projections was her. The person she is becoming, who I am beginning to catch glimmers of: immensely curious, eager to connect, earnest to figure out this thing of having a body and how to be in one, with a gaze that toggles between intense skepticism and warm wonder, with a smile and laugh that completely undoes me. And me, in her orbit: the person who I am becoming in her wake. The abstract story could never speak to the personal fleshiness of what it is to live life with her.

I am acutely aware of how quickly time is passing, all while our days and hours seem to balloon, stretched by their simplicity. Raising a child is the most mundane and biological thing a human can do and yet I am humbled by its relentlessness, its intensity, its totality. Our days are a collision of the mundane and the profound, the everyday and the exceptional. It feels impossible to capture and represent the bigness of it all and so I get swallowed by the minutae. As if the bigness of it all is too big for me to palpate, and so we go small. Perhaps the smallness is the bigness.

Since she arrived, life has been shaped by fragments: nights pocked by her wakings for milk or for closeness, sleep fractured into minutes and rare hours, the way my attention fragments and shifts registers in response to her cadence, fragments of my body still rearranging themselves after a somewhat traumatic birth, her developmental leaps like overnight downloads: discovering her hands, rolling to her side, the first shriek that becomes an unmistakeable giggle.

The books I’ve read since she arrived, in the dull light of my Kindle while breastfeeding her at all hours of night and day to keep from falling asleep, approach matrescence—a term coined by anthropologist Dana Raphael in the 1970s to describe the process of becoming-mother, as world-rearranging and body-rending as adolescence—with a fragmented form. In My Work, Olga Ravn subverts straightforward chronology, toggling among pregnancy and birth and early motherhood, embracing a loopy, autopoetic style. As its title suggests, Leslie Jamison’s Splinters (one of the most tender and yet piercing portrayals of early-motherhood I’ve read, and in my opinion her best work yet) is arranged in fractals of prose, a form invented by the birth of her daughter and the death of her marriage. And while not about motherhood, Sheila Heti’s Alphabetical Diaries (a book I think could only ever be published by someone like Heti) takes 10 years of diary entries and alphabetises them by sentence, revealing the repetitiveness and surprising narrowness of a mind’s obsessions over time—which was a salve to my early-postpartum brain, as I could devour sentence-by-sentence without having to digest a whole narrative. In all these books, time folds back on itself; story is told not in the dominant 3-part narrative structure (often critiqued as a Western patriarchal construct), but in a constellation of lived, fragmented intensities.

Before her arrival, one of the things I most feared was how becoming a mother would impact my relationship with writing. It’s a fear I confront every time I try to steal away time to write (and admittedly it does feel a bit like a theft). Reading and attempting to write in the shadow of early motherhood, I’m beginning to think writing in/about motherhood demands a different form. I’m quickly realising if I’m going to write at all, there is no room or time for the deliberation, over-analysis, perfectionism that so often characterised the way I used to meet the page. The shape of story must shift to hold a life as it, too, changes shape. Being response-ive and response-able to her, to us, means taking on new shapes, relinquishing the polished, the composed, the toxic mirage of the ever-elusive “perfect”. Nothing will get written or created in that space. And in a way, that is a huge relief to me. I want this for her. And I want this for me.

Below, I share some of my fragments from early matrescence, which together create some sort of mosaic, or perhaps an endless number of mosaics, depending on how they are arranged (and also how they are read).

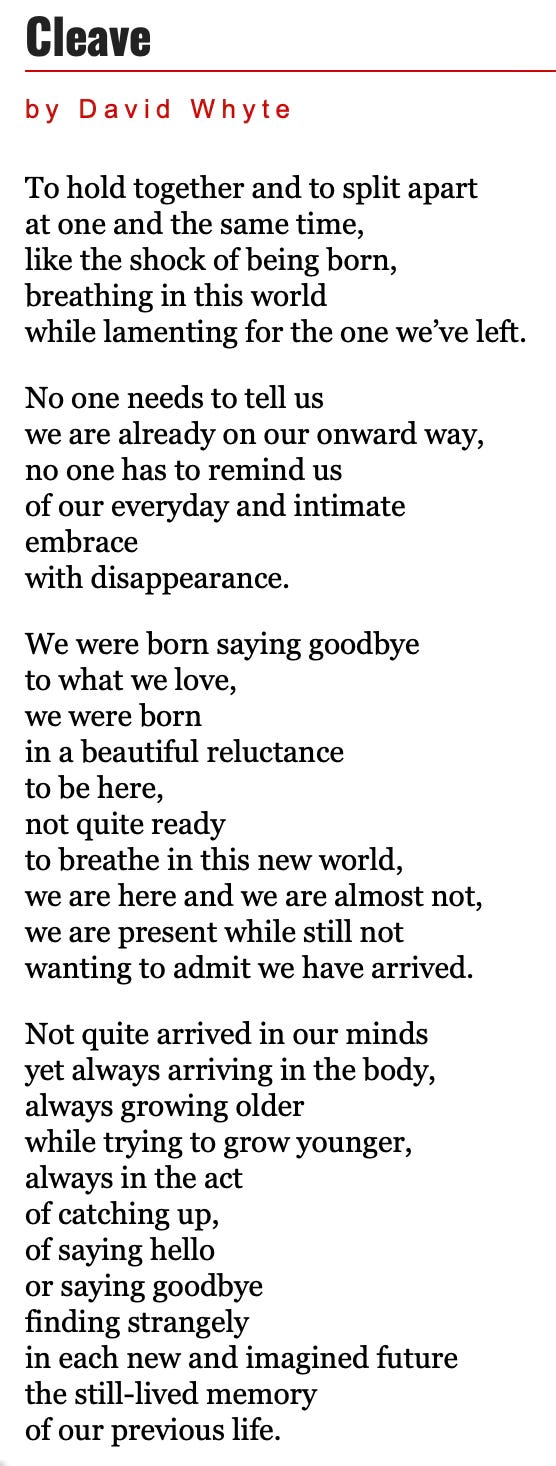

but first, a poem…

by the inimitable David Whyte (which I re-encountered thanks to the delightful

), that I’ve returned to often in these fragmented-and-yet-somehow-also-whole, supremely tender, first days of our life together:fragments of an early matrescence —

Ever since we brought her home from the hospital on her third day of life, she has turned her gaze toward the light. She looks up with intensity, as if studying: a ceiling lamp, a flame, a window. She is searching for the spaces where light gets in. Maybe I can learn from her: how to do this.

\\

Six weeks after birth, I take her to the forest in the bassinet and push her around with the top down. The late-winter branches, still leafless, split black fractals across a white sky. I think: high contrast. I think: this she can see. I tell her: these are called trees.

//

When a friend texts how are you feeling? I write her, among other things, my sense of self is completely dissolved — not in a devastating way, but in a fascinating way.

\\

I was prepared for the disruption. I was not prepared for the joy.

//

I thought that pregnancy and birth and having a baby would make all of it make more sense to me — how one body can beget/create another — but if anything it has made it all the more unfathomable. I look at her not-as-little body, the folds beginning to form in the soft flesh of her thighs, and cannot understand how all of her once fit into all of me.

\\

The fatigue is hollowing, in that it leads me into the caverns of myself: places I’ve never dared to go alone.

//

After spending an afternoon with us, a dear friend said It’s like she’s always been here, and it felt so true.

\\

I am learning more from my daughter about presence than I have from any yoga or meditation practice. This presence entails moving more slowly and simply than I ever have. This presence requires me to measure my days with different metrics — no, to not measure them at all. This presence is radical in its simplicity.

//

Being the external regulator of someone else’s nervous system is teaching me so much about my own.

\\

I am surprised how little I miss it: the breakneck speed of life before her, the rat-race of chasing enoughness through achievement.

//

When I have moments to myself I’m so hungry for them I don’t quite know what to do. These simple days, the margins of time I can steal away for myself go to writing, and I think that says something.

\\

There is so much of it I wish my writer-self would have captured, but to caretake and to not sleep and to sustain a life through the fluids of my body and to tend to a relationship and to write feels like too much for a single bodymind to hold.

//

When I left that hospital nearly a week after entering it, I left behind a self I will never be again.

\\

What even is a self? — I am beginning to wonder.

//

I’ve heard the early postpartum described as “ego death,” which feels apt.

\\

I voicenote a friend that I feel like I don’t know who I am any more, so far from the things that I thought defined me. I tell her all I have access to is the surprising joy I find in the simplicity of being with her. She responds, maybe the joy you’re finding in early motherhood is part of the new self that’s coming through. It strikes me that this strikes me.

//

Maybe the new self that’s coming through is more in integrity than the one you feel beholden to keeping up as some sort of construction anchoring you to built, made-up worlds.

\\

Maybe it is a self that is not formed in the opposition to the concept of other, but encompasses it.

//

Mothering her is showing me a fierceness I was never able to locate on my own behalf.

\\

I said to T one morning in the early weeks: I feel like I am growing away from the world, just as she is growing towards it. We are moving towards opposite poles, maybe this will be our forever journey. How somehow hers is to grow further and further from me into the world, just as I grow further and further into her, from the inevitable 24/7 work of caring for her. How beautiful and heartbreaking this is, at once. I see now, how the grief is inevitably entangled in the joy of this. How one doesn’t counter the other, but creates it. I am her harbor and she will forever be bravely sailing out, away. And I must learn how to swim, again, in this sea of our own making.

bits and bobs —

My friend Jacqueline Alnes’ book The Fruit Cure — a stunning hybrid memoir and narrative nonfiction about the body, running, neurological illness, fruit, and obsession — was published in January! I had the pleasure of interviewing Jacqueline for Electric Literature, and you can read our conversation — about the power of the stories we inherit and tell ourselves about our bodies — here:

Speaking of fragments, I loved Ann Friedman’s serialised essay about her pregnancy at 40

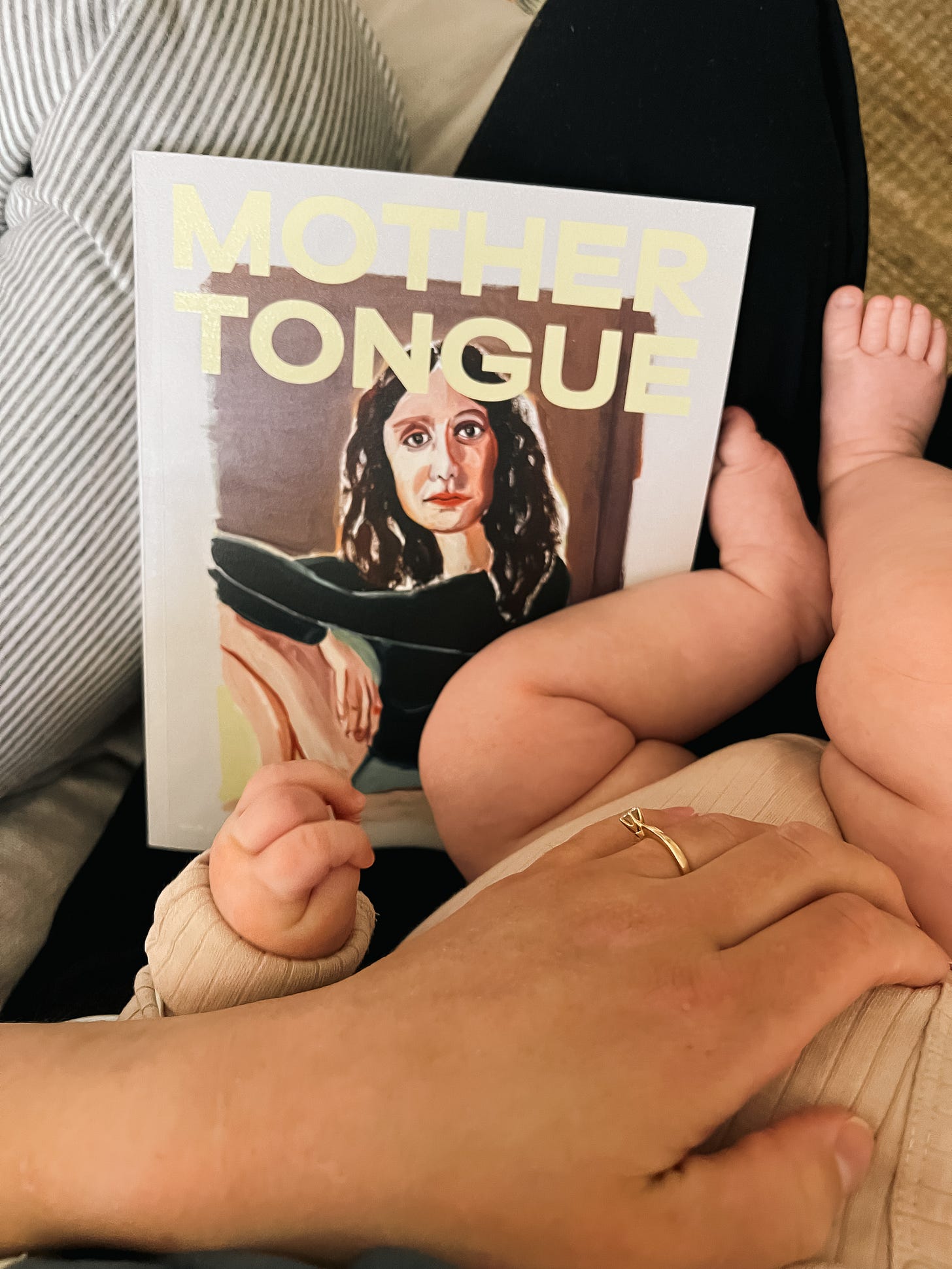

New favourite magazine

I deeply adored, and related to, Nada Alic’s recent essay on the newborn days in the LA Review of Books

What a beautiful reflection on your early weeks as a mother! I am excited to read the books you suggested too!

And it’s so true - fragmented reflections really do lend themselves so well to motherhood! I just write my first post on here about that too, how capturing those wandering thoughts has been so therapeutic in this wild ride of motherhood!