unlikely neighbors

one thing in relation to another. feat. Oliver Burkeman, Sheila Heti, Maggie Gyllenhaal, Elena Ferrante, writers and poets in Odesa, and med students reading poetry

To begin: a spring playlist from me to you, to listen to as you read April’s newsletter.

(I’ll now be sharing playlists seasonally, you can access and save the full list by clicking on the Spotify icon in the upper right corner):

A conversation with a dear friend last week reminded me that sometimes our toolboxes—as in, what usually helps, or, the way I do things—are better suited to a past self. Sometimes they need a reshuffle, sometimes an overhaul, in order to meet the life that’s uniquely ours in this very moment. And sometimes, the way we interact with and use these tools is what changes; not the tools themselves. What worked then does not always work now, and that does not mean something is wrong with you; it means that you are an adaptive growing human being whose needs and practices are adaptive and growing, too.

While I don’t think of it as a “tool,” I’m trying to apply that same tender flexibility to this newsletter as I enter a particularly full season of life: still writing to you, but in a way that feels sustainable and adaptive and kind and valuable to me and to you.

I’m juggling overlapping writing deadlines and staring down a spring in which conferences and lectures have resurfaced with abandon, among other exciting personal developments. So, in lieu of a coherent essay this month, I’m trying something different: a wander through unlikely neighbors (readings, film, encounters) that took up residence in me this month and had something to say to one another (with a writing prompt for you to do the same). A way to digest and process the random way in which stimuli wander in and out of you, not without leaving a trace.

unlikely neighbors

“Always: one thing in relation to another.”

My college photography professor’s words ring in my ears to this day.

The red wheelbarrow is in conversation with the stop sign. The sparrow, who flit across the frame at the exact moment the shutter closed, is speaking to the bee, perched in the foreground sipping honey. The child playing with her kite stirs a memory in the older woman eating lunch on a nearby bench—or was the memory stirred in you, the viewer? All of these: unlikely neighbors, for a moment, in proximity.

The photograph, I think he was trying to say, is made not by the single subject but by the intersubjectivity of things, the dynamic exchange between the two when placed in the same frame: one thing in relation to another. And then enter the viewer, the person who takes in the image, who projects meaning onto these relations from the fabric of their very own.

I often think of books and art and encounters this way: which ones happen to end up next to one another on any given shelf (beyond the bare fact of alphebatizing, or the color of their cover... no shade to anyone who likes to color-code their bookshelves) and what their unlikely neighboring says.

What would Audre Lorde say to Sheila Heti? Would Mario Vargas Llosa pick (another) fight with Gabriel García Márquez? Be careful who you put next to Hemingway.

If you are the bookshelf, who are the unlikely neighbors you’ve housed in the past few weeks?

Here are the unlikely neighbors who shacked up next to one another on the shelf of my mind—or walked into the same bar, if you will—this past month and had interesting, unexpected things to say to one another (and me):

Four Thousand Weeks by Oliver Burkeman

Pure Colour by Sheila Heti

The Lost Daughter (film version)

Conversations to the Tune of Air-Raid Sirens: Odesa Writers on Literature in Wartime

reading poetry with med students in a hospital

Below, I put an ear to this bookshelf and listen to what one thing in relation to another has to say, in this particular neighborhood: about mortality, time, parenthood and childhood, the point of art in war, and the intersections of art and science as they open into one another.

“mortality makes it impossible to ignore the absurdity of living solely for the future.” — Oliver Burkeman

In Four Thousand Weeks: Time Management for Mortals, Olive Burkeman, who used to write a column in The Guardian on productivity, argues that our collective obsession with ‘productivity hacks’ and ‘time management’ are convenient (if not self-sabotaging) attempts to delude ourselves about the bare fact of our mortality: that if we’re lucky we each get about 4,000 weeks on this planet (although who ever knows), a blink of an eye in planetary time, and that most of us will never accomplish all the dreams we’ve laid grandly before us.

[if short on time (ha) and you’d rather listen than read, this podcast covers the bolts of the book:]

Beyond a mere memento mori, Burkeman preserves optimism for what’s possible for our lives when we release our steeled grip on our schedules and goals and time and its most subtly lethal side effect: postponing of the sense of our lives happening until we arrive at the next goalpost. “Life will really start as soon as ____.”

While his insights stirred a humbling wake-up call to my own relationship to time and #goals, Burkeman still writes within (if not also against) a very particular Western and neoliberal framework of time: as something which an individual steers and bends to their will. While he alludes to caregiving in reflections about taking care of his infant son while writing this book, I found myself longing for a more nuanced conversation about other cosmologies of time and what we might learn from them — ones in which time is circular and cyclical, in which it’s not the sun that rises or sets but us that do this instead, and in which we’re all inevitably entangled with other beings whose needs, dreams, and survival are sometimes devastatingly at odds.

“but life is not a betrayal of life” — Sheila Heti

Enter: another cosmology of time.

In Heti’s stranger-than-fiction world that is Pure Colour, we are just living in the first draft of humanity, and three art critics in the sky are asking for critiques to improve upon it. Humans are fish, bears, or birds—depending on how they relate to life and care and structure and creativity—and the main character ends up, temporarily, cohabiting in a leaf with her recently deceased father. Time and death are both transformed by a magical realism that still feels uncannily inhabitable.

Heti wrote most of Pure Colour in the wake of her father’s passing, and her meditations on guilt and desire and art and child-parent relations are arresting and achingly human. This one will stay with me for a very long time (I know I mentioned it to you last month). I think it is one of my favorite novels.

I devoured most of Pure Colour on the planes from time spent home in Bend with my parents to Santa Fe for work, and mostly in tears, watered by this passage in particular:

“It is easy to feel love for one’s child. Nothing on earth is easier. A father often has a special love for a daughter. It is natural to want to shine your interest and pride onto your own child. It is simple to love one’s own creature. But that is a debt the child can never repay—to have been given all that love and care. It feels completely imbalanced.

There is a ruthlessness to life. It seems to lack balance—and in its particulars, it does. None of us is able to stand far back enough from life to see the balance that somehow exists. The child is never who the parent wants them to be, and they must not be… But that is entirely necessary. That is how the world changes, how values and criticisms evolve and change. A child must follow the rules of her own being. A parent can never truly understand what those values or rules are. A child is an alien to the parent, which hurts the parent a little. The child’s whole life can feel like a betrayal. But life is not a betrayal of life.”

"the bits that I find beautiful about them are the bits that are most alien to me." — Leda, The Lost Daughter

It is not always, for everyone, simple to love one’s own creature (to riff off Heti’s words).

Leda, the main character of The Lost Daughter, proclaims herself an “unnatural” mother, grappling with the frictions of care and self-actualization, and ultimately abandoning her two daughters for several years in pursuit of desire, freedom, writing, and a career in academia.

Maggie Gyllenhaal’s filmic adaptation of the Elena Ferrante novel of the same name, The Lost Daughter, finally made its way to theaters in Sweden, and I finally saw it. I know many in the States have already seen it—I’ve already heard from friends, both mothers and non-mothers, how triggering and unsettling it can be, so I entered the theater somewhat braced.

This one shook me. There is so much, too much for here, I could say about it. Not yet a mother myself, but very much curious/apprehensive about representations (and realities) of art and creativity at odds with caring for one’s own creature(s), I did appreciate the film for surfacing a language that feels painfully suppressed among caregivers, about sometimes-irreconcilable tensions. I don’t feel equipped to say much more than this now, except that it jolted me from Heti’s reflections of parenthood, from the perspective of a child, into the perspective of a mother who defies and rewrites most of the available narratives at hand about motherhood.

“A poet should be a vibrating string that responds to everything happening around us.” — Anna Streminskaya

Odesa Writers on Literature in Wartime

What is the role of words on a page when bombs are dropping mercilessly on maternal hospitals and civilian communities?

I know many are grappling with different iterations of “what’s the point” as we take in the horrors unfolding in so many corners of this world.

This interview series in The Paris Review gathers writers and poets in Odesa, Ukraine, speaking about the role of art and words in wartime. Their words speak for themselves:

“My wish for you, is to never have the experience of going about your day to the rhythm of constant air-raid sirens. The pain is experienced by the city and by Ukraine as a whole. This pain passes constantly through the writer’s breastbone.” — Yevgeny Golubovsky

“I come back to Heine, who said that each new epoch needs a new kind of reader, needs new sets of eyes.” — Ganna Kostenko

“A strange feeling: everything around me now is what I once used to read about in books on war, thinking how wonderful it was that I lived in a different time. I don’t live in a different time. This movie is now the life of my family, my city. It is a very mediocre movie. I want to turn on the lights in this theater.” — Marina Linda

“In times of war, writing goes badly. What can you do? Your mind refuses to make sense of what’s happening.” — Nail Muratov

“A poet should be a vibrating string that responds to everything happening around us. I am following what my poet friends are writing, and the level of their poetry has risen—the language has become very precise, strong.

There are no words nor justifications for what the Russian Army is doing in Ukraine—in Kharkiv, in Mariupol’, in other cities. Still, the task of poetry is to find words even when there are none.” — Anna Streminskaya

To find words even when there are none.

reading poetry in a hospital with doctors-to-be

I suppose this is a strange place to land, at the end of the bookshelf (or bar), not with pages or screens or words but IRL with other humans, but this encounter spoke to the above unlikely neighbors in a way that expanded my aperture.

I’m preparing to teach Narrative Medicine and Medical Anthropology at the medical school here this fall, and I’ve been shadowing literature seminars alongside med students.

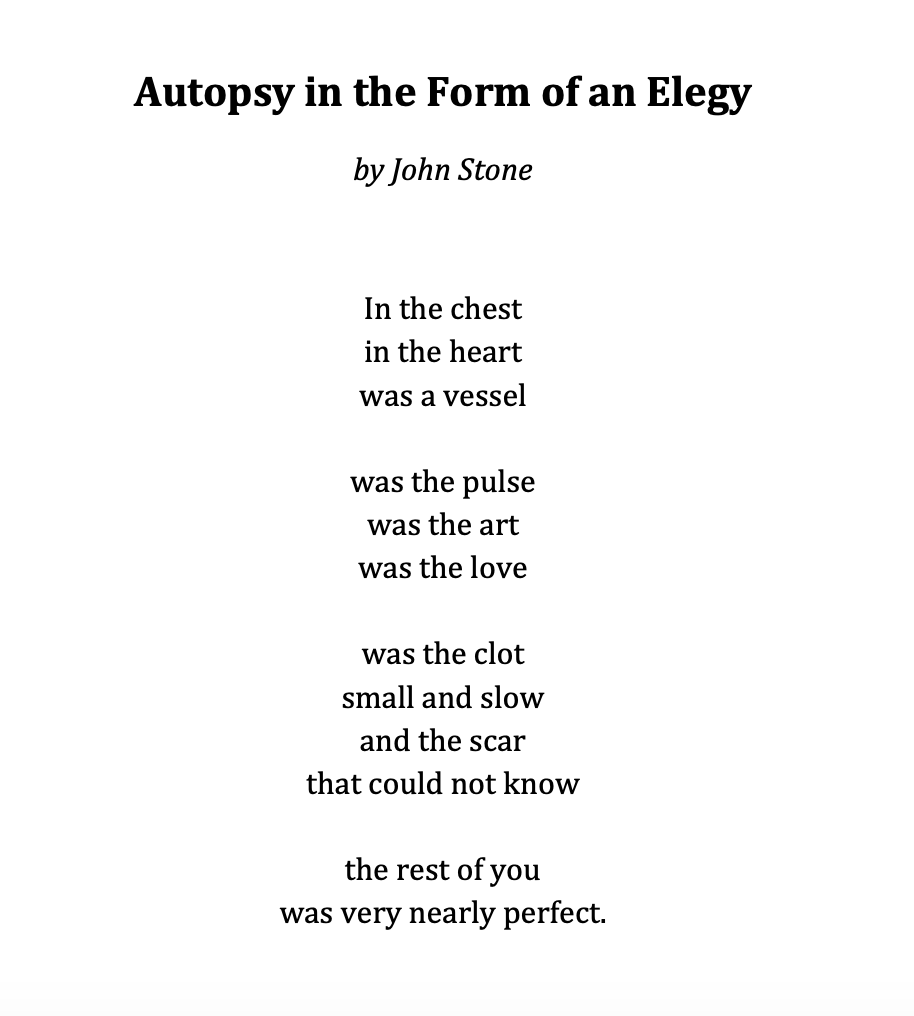

Last week, second-year med students arrived to a poetry seminar on the heels of their very first autopsy. For many, this was their first encounter with a nonliving body. The selected poems — some Swedish, some English, some by doctors, others by non-doctors — dealt with life and death, bodies, and what it is like to behold them. Light topics such as this.

I witnessed firsthand the shift in tenor and possibility for conversation among the students once poetry swung the doors wide open. Emotions and interpretations surfaced in expressions that clinical language couldn’t give voice to. The possibility for multiple conflicting feelings coexisting at once felt permissible, palpable. I sensed the room exhale and, in doing so, expand what it could hold.

I thought I’d share one of the poems here with you, to close:

It’s only after encountering and experiencing all these unlikely neighbors in relation that I see the threads and throughlines, among which: the unavoidable (but painstakingly avoided) fact of mortality, the role of what we do/make in its wake, how this contends with who we are/want to be and survive in the world, alone and with others, what role art plays in worlds and lives teetering on the brink, and the human work of finding words when there are none.

What this one viewer, responding from her small slice of experience, sees in this frame, is that language and representation matter deeply, vitally, if only to give us a medium through which to witness and pay attention and, most vitally of all, feel.

writing prompt:

What unlikely neighbors have inhabited the bookshelf of your mind in the past month?

Neighbors can take all shapes and forms — they don’t have to be entire books or articles or films. They can be conversations, images, even single sentences or words.

What do you see, when you place them in the same frame?

What do they have to say to one another?

What unfolds, when one thing exists in relation to another?

And: have any of my unlikely neighbors also been yours? I’d be so curious to hear how these words/stories landed with you. Feel free to share your reflections below — I always love to hear and connect over different interpretations and experiences of art.

I have exciting news to share: We have an app! You can now read The Liminal in the new Substack app for iPhone (if you don’t have an Apple device, you can join the Android waitlist here).

With the app, you’ll have a dedicated Inbox for my Substack and any others you subscribe to. New posts will never get lost in your email filters, or stuck in spam. Overall, it’s a big upgrade to the reading experience.

Did this issue resonate with you, or might it land with someone in your orbit? You can share a screenshot of any portion on social media tagging @liminalliety, or use the button below to share this article.